Introduction

One of the most produced cerials in the world is also one of the most difficult and dangerous to transport. In this comprehensive loss prevention article, we will cover important topics such as vessel requirements and cargo handling as well as look at some recent incidents in wheat transporation.

In 2016/17, the total production of wheat was over 735 million tones, making it one of the most produced cereal in the world, and is now said to be grown on more land area than any other food. Compared to iron ore and coal, grain is an agricultural commodity which is seasonal in its trade and irregular in both volume and route and therefore its carriage is difficult to be optimized and depends heavily on general purpose tonnage from the charter market.

Types of wheat

Over thousands of years of cultivation, numerous forms of wheat have evolved.The table below lists the classification system used in the United States. Other countries may use other classification systems.

| Type | Details | Used for |

| Durum | Very hard, translucent, light coloured | Flour for pasta and bulghur |

| Hard Red Spring | Hard, brownish, high protein wheat | Bread and hard baked goods |

| Hard Red Winter | Hard, brownish, mellow high protein | Bread and hard baked goods |

| Soft Red Winter | Soft, low protein | Cakes, pie crusts, muffins, biscuits |

| Hard White | Hard, light-coloured, opaque, medium protein | Bread and brewing |

| Soft White | Soft, light-coloured, very low protein | Pie crust and pastry |

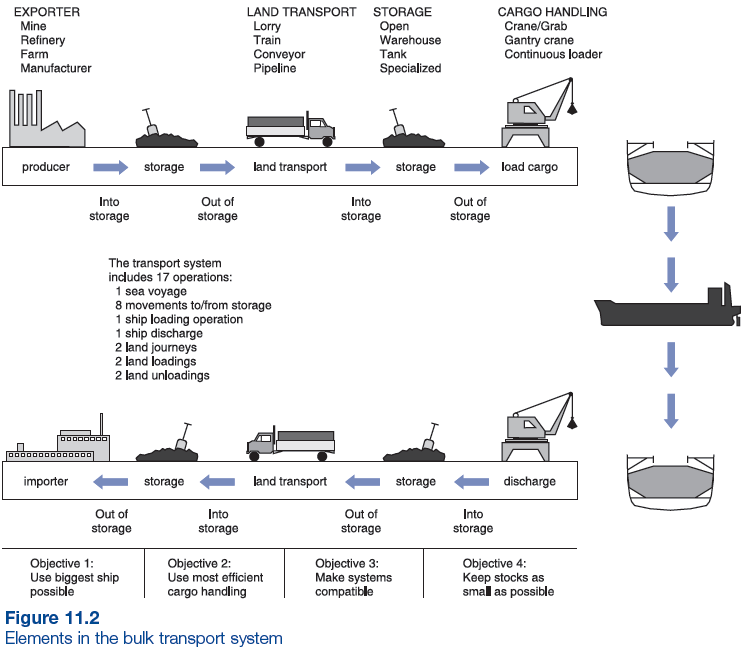

The typical wheat supply chain

Source: Maritime Economic, 3rd edition, chapter 11, figure 11.2

The top exporters and producers of wheat in 2015 were:

| Top 5 producers | Top 5 exporters | Top 5 importers |

| China | Canada | Italy |

| India | USA | Algeria |

| USA | Australia | Egypt |

| Russia | France | Indonesia |

| France | Russia | Japan |

As you can see from the list, wheat is often shipped over long distances. The supply chain is similar to the figure above. It starts out on a farm, where wheat is harvested and stored locally, or transported by a truck to a storage elevator. From the storage elevator the wheat is gravity fed onto a railcar and shipped to port where it is offloaded and then reloaded to another storage elevator, usually by conveyor belts. Here, the grain is accumulated until there is sufficient load for a merchant ship. At the other end of the voyage the process is reversed and the grain is offloaded from the ship into a storage elevator (silo etc.), and then shipped to a flour mill or feed compounder for further storage. From the storage it moves to a grinding facility via a conveyor or an air slide, and finally the finished products are packed for the consumer market or shipped in bulk to other end users.

Charterparties

In the grain trade the following types of voyage charter forms are generally used, although with some modifications to suit local circumstances. The charter party forms can be very specialised to apply to certain loading areas.

| Name | Codename | Commonly used in |

| North American Grain C/P | NORGRAIN | USA & Canada |

| Baltimore Form C | BFC | USA & Canada |

| Continent Grain C/P | SYNACOMEX | European Continent |

| Australian Wheat C/P | AUSTWHEAT | Australia |

| Grain Trade Australia V/C | AUSGRAIN | Australia |

| Chamber of Shipping River Plate C/P | CENTROCON | South America |

| Norgrain South C/P | NORGRAIN S | South America |

| Standard Grain Voyage C/P | GRAINCON | General |

Vessel requirements

SOLAS regulation VI Part C (Regulation 9) (Requirements for cargo ships carrying grain) provides that a cargo ship carrying grain must hold a Document of Authorization as required by the International Grain Code. A ship without a Document of Authorization must not load grain until the master satisfies the Flag State Administration, or the SOLAS Contracting Government of the port of loading, that the ship will comply with the requirements of the International Grain Code in its proposed loaded condition. Without the certificate, the vessel will be refused entry into port to load cargo.

Before loading

Before loading, the holds must be examined for potential defects such as rust scale, insect infestation, oil sludge, and water. The ship must be substantially clean, dry, and ready to receive grain before the loading can begin. Almost all the above charter parties have provisions for vessel inspection before/during loading. For example:

GRAINCON paragraph 3. Vessel Inspection:

The vessel shall pass the inspections of the relevant Port, State or National Authority and/or Grain Inspection Bureau at the first or sole port or place of loading, certifying the Vessel's readiness in all compartments to be loaded with the cargo covered by this Charter Party. If the vessel completes loading at a port in a different country than the first loading port, she shall pass the inspections of such subsequent national and/or regulatory bodies as may be required. The cost of such inspections shall be borne by the Owners and should the Vessel fail to pass inspections, the time from such failure until the Vessel has been passed shall not count as laytime or time on demurrage. Unless the conditions of Clause 18(b) apply the Master’s notice of readiness as the first or sole loading port, shall be accompanied by the certificates issued in accordance with this Clause.

NORGRAIN paragraph 3. Vessel Inspection:

Vessel is to load under inspection of National Cargo Bureau, Inc in USA ports or the Port Warden in Canadian ports. Vessel is also to load under inspection of a Grain Inspector licensed/authorized by the United States Department of Agriculture pursuant to the U.S. Grain Standards Act and/or of a Grain Inspector employed by the Canada Department of Agriculture as required by the appropriate authorities. If vessel loads at other than U.S. or Canadian ports, she is to load under inspection of such national and/or regulatory bodies as may be required. Vessel is to comply with the rules of such authorities, and shall load cargo not exceeding what she can reasonably stow and carry over and above her Cabin, Tackle, Apparel, Provisions, Fuel, Furniture and Water. Cost of such inspection shall be borne by the Owners.

AUSTWHEAT paragraph 10. Survey at loading port:

Before loading is commenced the Vessel shall pass the customary survey of an Australian Commonwealth Government Marine Surveyor, and a recognized Marine Surveyor approved by the Shippers. Additionally, the Vessel shall pass any survey/inspection required under State and/or Federal Legislation.

Charter parties may also state that representatives from the charterers, shippers, receivers and owners or their respective agents shall have the right to be on board whilst loading and/or discharging for the purpose of inspecting the cargo, checking the weight(s) and supervising their interests. Surveyors should monitor the loading closely, and take samples at certain intervals.

Holds

After the carriage of contaminating (coal, ores, cement, sulphur, etc.), odor-tainting or pest-infested cargoes, holds must be cleaned, disinfected, deodorized and ventilated. An inspection certificate confirming fitness for loading should be provided. The holds must be “Grain Clean”. Details of at least the three previous cargoes will be required. Before loading, holds/containers should also be examined by an independent inspector for infestation by pests of any kind and an appropriate certificate obtained. It is also very important to separate different types of grains if they are carried in the same vessel. To avoid shifting of cargo, the grain surfaces must be reasonably trimmed. All non-working hatches of the cargo spaces into which the cargo is loaded or to be loaded should be closed.

Most charter parties also list out rules for Cargo Spaces:

GRAINCON paragraph 12. Cargo Spaces:

Cargo shall be loaded in unobstructed main holds only, unless the Owners require, solely for trim and stability purposes, cargo to be loaded into wing spaces, always provided the cargo can bleed into centre holds. Wing spaces are to be spout trimmed; any further trimming in wing spaces and any additional expenses in loading or discharging to be for the Owners’ account and additional time so used is not to count as laytime or time on demurrage.

Most charter parties also lay down rules and cost allocation for separation and securing the cargo.

Additionally, charter parties commonly list out provisions for fumigation of holds. For example:

SYNACOMEX 2000 paragraph 11:

Charterers have the liberty to fumigate the cargo on board at loading and discharging port(s) or places en route at their risk and expense. Charterers are responsible for ensuring that Officers and Crew as well as other persons on board the Vessel during and after the fumigation are not exposed to any health hazards whatsoever. Charterers undertake to pay Owners all necessary expenses incurred because of the fumigation and time list thereby shall count as laytime or time on demurrage. When fumigation has been effected at loading port and has been certified by proper survey or by a competent authority, Bills of Lading shall not be claused by Master for reason of insects having been detected in the cargo prior to such fumigation.

NORGRAIN paragraph 16:

If after loading has commenced, and at any time thereafter until the completion of discharge, the cargo is required to be fumigated in vessel’s holds, the Owners are to permit same to take place at Charterer’s risk and expense, including necessary expenses for accommodating and victualing vessel’s personnel ashore. The Charterers warrant that the fumigants used will not expose the vessel’s personnel to any health hazards whatsoever, and will comply with IMO regulations. Time lost for the vessel is to count at the demurrage rate.

Sampling

By using a diverter-type (D/T) mechanical sampler, a certain amount of the grain lot is drawn out for sampling. Installed at the end of the conveyor belt, it draws samples by periodically moving a device through the entire grain stream. After a primary sampler, the grain flows into a secondary sampler to reduce the size of the sample and from here it moves to a collection box or bucket inside a laboratory under the control of official personnel.

On completion of loading, the hatch covers should be sealed. It is important to keep holds weather tight. If wetting is caused by salt water, drying out and reconditioning the cargo may not be financially viable and a total loss could result.

Inspection Procedures

The inspector periodically examines the samples collected to check for objectionable odors and insects. The inspector sieves the entire sample to perform a visual examination. After passing preliminary tests, the sample is divided into two portions of approx. 1350 grams each, one work sample and one file sample. The work sample is used to determine the moisture and all grading factors. The file sample is maintained in a moisture proof container at the laboratory, locked in for 90 days after the inspection is completed. The sample is available for review in the event of any questions regarding its quality.

The sample may then be further broken down to determine the quality of the wheat. It is also important to check the cargo’s moisture content.

Cargo handling

Weather

In damp weather like rain or snow, the cargo must be protected from moisture, since wetting and extremely high humidity may lead to mold growth, spoilage and self-heating due to increased respiratory activity. The cargo should not be wetted at any stage. Do not simply give-in to stevedores assurances that the loading will be ok in such conditions.

Bills of lading

If the master is being pressured into signing a “clean” B/L you should contact the local P&I correspondent and issue letters of protest. Remember unclean bills have consequences. Members should be aware that P&I cover can be prejudiced if clean bills of lading are issued where the Master knows cargo is wet or damaged. Please refer to Skuld Rule 5.2.5

A protest should be issued if the draft surveys are different from the shipper’s figures. Members may wish to place charterers on notice of their potential liability for shortage claims. Inserting figures known or suspected to be inaccurate may prejudice P&I cover. Please refer to Skuld Rule 5.2.5

Risk factors

When shipping wheat, there are a lot of factors that need to be taken into consideration. The use of surveyors and inspections are essential.

Angles of Repose

Wheat is predominantly transported as bulk cargo, but on some occasions transported in bags or even Containers. Wheat/Grain is said to be one of the most difficult and dangerous cargoes to carry in bulk. Most cargoes have an angle of repose (slip angle) of 20° from the horizontal, meaning that if the ship rolls more than 20° the cargo will shift. Eventually the ship may capsize. Because grain cargoes are liable to shift, heavy emphasis is placed on the stability of carrying ships and the proper trim of the cargo in the holds.

Temperature / Moisture / Water Content

Safe wheat carriage requires certain temperature, humidity/moisture and ventilation conditions. There is no lower temperature limit and the favorable travel temperature is around 20°C.

Molds reach optimum activity level in the range between 20° to 30°C. At temperatures over 25°C the metabolic processes increase, leading to increased CO2 production and self-heating of the wheat.

Wheat can be classified by moisture content:

| Water content | Up to 15% | 15-16% | 16-17% | 17-18% |

| Designation | Dry | Medium Dry | Moist | Wet |

Moisture causes mold, mustiness and fermentation, agglomeration, self-heating and a risk of germination (premature sprouting). If this happens, the product may no longer be suitable for milling into flour, but instead only for producing spirits. Problems with moisture can be prevented by suitable pre-drying of the wheat.

Wheat with a moisture content of over 16-17% can rapidly produce an excessively damp atmosphere within the hold. Individual clusters of damp wheat may cause considerable damage to the cargo. Wheat in such clusters has a tendency to self-heat. Damp wheat then appears in boundary layers, allowing the process to continue further in the holds during carriage at sea.

At moisture levels of over 17%, swelling occurs in addition to fermentation, mould, rot and self-heating. Seawater damage may result in structural damage to the ship due to the swelling in the hold. Where such damage is suspected, a sea water test should be carried out using the silver nitrate method.

For North Atlantic voyages, a moisture content of 13% is the optimum value and the grain is dry for shipment. During the lower temperatures in the winter, 15% is possible. At low moisture content, the intensity of respiration is low at all temperatures. Even at 25°C, the respiration intensity is low at moisture levels up to 13%. If the moisture content is above 15% and elevated temperatures also occur, respiration becomes more intense.

Prior to loading, the moisture content should be checked by an independent inspector and a certificate provided. The certificates should state not only that appropriate measures have been carried out but also how and with what they were carried out and at what level of success. Lumber used for grain bulkheads must be air dry, and moisture content must not be over 15%.

Ventilation

Ventilation is essential until the cargo has been unloaded from the ship, and should not be stopped while the ship is waiting to berth. For the purpose of defending against cargo claims, maintaining accurate ventilation records on the vessel will be essential. It is important to record both periods of ventilation and periods when ventilation is not possible or suitable (and why this is so, e.g. for bad weather).

The main purpose of ventilating a wheat cargo is to minimise moisture within the cargo hold by replacing moist air with relatively drier air; this helps to prevent the formation of ship's sweat and cargo sweat, both of which are likely to cause damages to the cargo. Special care should be taken on voyages to avoid both cargo and ship's sweat.

Wheat releases water vapour constantly, which needs to be dissipated by ventilation. A link exists between the need for ventilation of wheat / grain and its moisture content. Cargo with a moisture content under 14% may not need extensive ventilation, but up to a moisture content of 15% surface ventilation is recommended. Depending on the nature of the cargo and the climatic conditions encountered during the voyage, proper ventilation practice has proved to be a vital aspect in avoiding claims.

Cargo sweat

Cargo sweat occurs when warm moist air comes into contact with the surface of a cold cargo. This could happen when a wheat cargo in bulk is loaded in a cold region for passage to a relatively warm region. As the vessel steams towards the warm region, the temperature of its structure will increase gradually following that of the sea water and air. Since wheat has a much lower thermal conductivity than steel, the cargo would warm up more slowly, leading to its temperature being lower than that of the external atmosphere during the voyage. In circumstances where the dew point of the external air is higher than the temperature of the air within the hold and ventilation is applied, warm moist air could enter the hold and condense onto the cooler surface of the cargo, forming cargo sweat.

To prevent cargo sweat, in general no ventilation should be carried out when entering a warm climate from a relatively cold climate. It is safe to carry out ventilation only when the temperature of the stow is higher than or equal to that of the external air, or if the dew point of the external air is lower than that of the atmosphere within the hold.

Ship's sweat

Ship's sweat occurs when warm moist air comes into contact with cold ship's steelwork inside the cargo hold. For instance, a wheat cargo in bulk is loaded in a warm region for passage to a relatively cool region. As the vessel enters into the cold climate, the temperature of sea water and air begins to fall. The ship's steel structure, being a good thermal conductor and in direct contact with the sea water and air, would adopt to those temperatures and gradually become cold from the outer hull to the hold structure, whilst the cargo itself, being a poor thermal conductor, would only get cooler slowly while tending to maintain its higher loading temperature, especially toward the insulated centre of the stow. Warm moist air would then rise from within the stow to the underside of the hatch covers, as well as to the sides of the hold due to convection. If this air encounters any ship's steelwork which is at a temperature below the dew point of the cargo hold air, then moisture will condense on it, forming ship's sweat.

Additionally, ship's sweat can occur because of local heating or cooling events within the vessel. If the cargo contains natural moisture, e.g. wheat, then any heating of the cargo by an external source such as a fuel oil tank or an engine can also result in the formation of condensation onto cold structures. Another scenario to bring about condensation, would be if refrigerating units are able to cool the ship's steel structure below the dew point of the air within the hold, leading to condensation on the cold steel.

The most effective way to prevent ship's sweat is to ensure that a wheat cargo is sufficiently dried before loading. If a shipment of wheat cargo with high moisture is loaded in high temperature, the dew point of the atmosphere within the hold would be higher than that of the external air, resulting in ship's sweat. Some suggest that a moisture content below 13% is considered a safe level for storage.

Ventilation should also be applied when either of the following rules are fulfilled:

Dew Point Rule

According to the Dew Point Rule, ventilation should only be carried out when the dew point of the external air is lower than the temperature of the air within the hold, during fine weather and in the absence of sea spray. This is because if external air with a relatively higher dew point is allowed to enter the hold, cargo sweat will result.

Three Degree Rule

The so called three-degree rule is commonly applied on agricultural cargoes when deciding whether to ventilate or not. It involves a comparison between the cargo loading temperature and the temperature of the external air during the voyage, with the intention that ventilation should only be given when the external temperature is at least 3°C cooler than the average cargo loading temperature. While this technique assumes that the cargo temperature will remain constant for the entire voyage, a number of temperature readings should still be taken regularly during the loading and the voyage for comparison.

Self-heating

Especially in freshly harvested grains with an average moisture contents of 14% or greater, there is a risk of self-heating; given the differing stages of ripeness of the individual grains; some of them have higher moisture contents. They are the starting points for moist spots which expand continuously and finally encompass the entire cargo of grains with a major rise in temperature.

Gases

Metabolic processes continue after harvesting the wheat. The wheat absorbs oxygen (O2) and excretes carbon dioxide (CO2). Respiration may cause life-threatening CO2 concentrations or O2 shortages in the holds. Ventilation and gas measurements must be carried out before anyone enters the hold. It is important to find out what type of grain is about to be carried and if it gives off any dangerous gases.

Strict rules for entering enclosed spaces on vessels must be followed.

Odour

Gasses and aroma substances are readily absorbed by the grains. For this reason, holds must be completely odour-free and deodorization must not be carried out until immediately before loading.

Insect infestation

Wheat may be infested by cereal pests during storage and transport. Inadequately cleaned warehouses and holds are usually the root cause of insect infestation. Infestation may result in self-heating which ultimately gives rise to depreciation or even total loss.

Cargoes will need to be fumigated, and in case significant delays occur at any stage in the voyage thought would have to be given to checking and possibly re-fumigating the cargo as insect populations and other pests can multiply rapidly in a cargo hold of wheat.

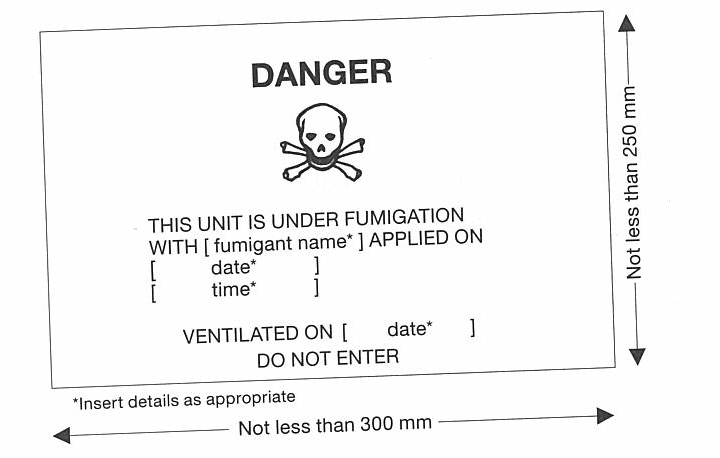

Fumigation of wheat cargo

The main purpose of wheat cargo fumigation is to exterminate any live pests within an enclosed space, thereby avoiding the spread of diseases, and preventing commercial or other losses as a result of any damage to the vessel, the cargo itself and any subsequent cargoes thereafter. Two of the most widely used fumigants are Methyl bromide and Metal phosphide (Phosphine).

The fumigation process involves firstly the release and dispersal of chemicals (fumigants) at lethal doses, to kill any targeted pests, then ventilation of the space and removal of residues for safe human access.

Fumigation Rules and Regulations

Since fumigant gases are poisonous to humans and require special equipment and skills for application, they should be used only by specialists and not by the ship's crew. Fumigation operations are governed by a number of national and international rules and regulations. The preparations, procedures and safety precautions of such operations are also detailed in numerous guidelines, including the ones listed below:

- IMDG Code – Recommendations on the Safe Use of Pesticides in Ships

• Revised Recommendations on the safe use of pesticides in ships – MSC.1/Circ.1358

• Recommendations on the safe use of pesticides in ships applicable to the fumigation of cargo holds – MSC.1/Circ.1264

• Recommendations on the safe use of pesticides in ships applicable to the fumigation of cargo transport units – MSC.1/Circ.1361 - The International Maritime Fumigation Organisation (IMFO)

• Code of Practice on Safety and Efficacy For Marine Fumigation - SOLAS – Chapter VI Carriage of Cargoes Part A – General Provisions Regulation 4

- GAFTA Trade Assurance Scheme – Code of Practice for Fumigation and Pest Control

- United States Department of Agriculture – Fumigation Handbook

Fumigation can be conducted before loading, before sailing, or during the voyage (in transit) by a competent fumigator who is trained and certified to use or supervise the use of fumigants and to carry out ventilation activities. Prior to the fumigation, the vessel should be inspected to confirm its suitability for such operations. The crew should be disembarked until the fumigation is completed and the vessel is certified as "gas free" by an authorised person. During the operations, a warning sign should be displayed and any unnecessary boarding should be prohibited.

It is very important that the right dosage of fumigant is used and the amount is always calculated by an authorised person / qualified operator.

The master should be provided with written instructions by the fumigator-in-charge on the type of fumigant used, the hazards to human health involved and the precautions to be taken. Owing to the highly toxic nature of all commonly used fumigants, these instructions should be followed carefully. Such instructions should be written in a language readily understood by the master or his representative.

Fumigation in cargo holds in transit

Phosphine (Metal phosphide) is the only fumigant allowed to be used in transit according to the "IMDG Code – Recommendations on the Safe Use of Pesticides in Ships". It is a highly toxic gas commonly used when fumigating a partly or fully loaded cargo hold during a voyage. At the load port, tablets of Aluminium or Magnesium phosphide are placed on the top, within or at the bottom of the stow in a cargo hold. When they react with moisture in the air, phosphine gas is formed and dispersed within the hold atmosphere. The process continues during the voyage until the hold is ventilated, the fumigant residues are later removed at the discharge port.

Fumigation at the load port prior to sailing

Similar to fumigation in cargo holds in transit, phosphine is frequently used when fumigation is required on board prior to sailing. The same procedures as for in transit fumigation should be followed.

Fumigation at the discharge port prior to discharge

Methyl bromide is often used when a rapid fumigation is required (usually within 24-48 hours) while the vessel is in the confines of a port. Since it is a highly toxic gas which could be absorbed or desorbed by cargo, it should only be used when a strong ventilation system is available to remove all lethal gases before the discharge of cargo. However, the use of methyl bromide is not recommended due to environmental reasons and is banned in some countries. Instead, phosphine can be used but the process would normally take 1 to 2 weeks, which is much longer when compared to methyl bromide. The same procedures as for in transit fumigation should be followed.

Prior to discharge ventilation must be done, forced if necessary, to reduce any gaseous residues below occupational exposure limits set by the flag State regulations for inside the free spaces.

Safety concerns

To ensure a safe and effective fumigation, Recommendations on the Safe Use of Pesticides in Ships in the IMDG Code must be referred to and strictly followed, as well as any laws and regulations of flag and port state, together with the manufacturer's instruction for the fumigants. The personnel involved in the fumigation operations, including the Master, the crew and the fumigators must be familiar with these Recommendations. In case any symptoms of phosphine poisoning occur, such as nausea, vomiting, headache and cough, the person should leave the compartment and seek medical advice immediately.

After discharge

It is common to analyse the cargoes for bacteria, etc. In case of concern, discharge sampling and surveying should be carried out on behalf of the vessel, for both quality and quantity issues.

Recent incidents

Over the years the Association has seen many claims arising out of the transportation of wheat/grain cargoes:

Rain during loading operation

- The Captain told local stevedores to stop loading and close the hatches as he feared it was going to rain.

- Stevedores ignored his request and continued loading.

- Due to heavy passing rain showers, cargo in two of the holds were wetted.

- Surveyor attended the vessel, and in addition to some wetted cargo, he found a significant amount of threads/ garbage mixed with the loaded cargo.

Cargo damaged by sea water

- During discharge at the Aden Gulf Terminal, a shipment from Argentina was found to be partially damaged because of sea water leaking into the holds.

- Owners were held responsible for the damage.

- Another vessel loaded in India and discharged in Jebel Ali, UAE.

- The captain signed a clean bill of lading for 2500MT of wheat in hold 2.

- At discharge, they found 65MT of the cargo discoloured, mouldy and smelly due to seawater leaking in to the cargo hold.

- The vessel was arrested and not released until the Club issued a LOU, and later the case was settled commercially between the parties.

Cargo damaged by heat

- During discharge in Chittagong, 150MT was found damaged due to overheating.

- The cargo was discoloured, burned, and emitted a burning smell.

- A fuel oil tank used for heating HFO was situated right below the affected cargo holds.

Cargo shortage

- Cargo receiver claimed a shortage of 200MT of wheat when the vessel discharged in Tunis.

- He also threatened to arrest the vessel and required a bank guarantee, which was put up by the Club.

- After completion of discharge the total shortage was found to be only ¼ of the originally claimed shortage, 50MT.

- Bank guarantee charges are very high. In some cases, consideration should be given to whether the claim can be settled quickly.

Cargo infested by insects

- The vessel sailed from Paranagua, Brazil to the Philippines with a cargo of 44500MT feed wheat.

- During discharge in Subic Bay, when opening the hatch covers, the cargo surveyor found live crawling insects in the cargo.

- It was found that during fumigation at the load port, the fumigants was not evenly scattered/ thoroughly mixed with the cargo.

- As fumigation is usually a charterer’s responsibility, care should be taken to pursue charterers for an indemnity.

- In this respect, members need to review before entering into their charters that charterers are financially secure.

Contamination claims

- In recent years, there have been some cargo claims made on grain cargoes in Iran.

- During discharge, the receivers claimed that cargo in one hold was contaminated with the e-coli bacteria.

- After three positive tests by a local authority laboratory, the owner had the cargo tested in the UK, and the test was negative.

- Ensuring pre-shipment tests and certificates is vital when trading to countries that have rigorous local regulations on food quality.

Hot tips

Before fixing

- Is your charterer financially sound?

- Does your charterer have P&I cover with an IG club?

- Is your charter party such that it protects your interests?

- Who has liability in the charter party for loading, fumigation, ensuring proper certificates and discharge?

Vessel

- Vessel and holds must meet requirement in the Grain Code

- The hatch covers are to be in weather-tight condition

- Necessary hatch cover sealing materials are to be carried on board / used to prevent water ingress to the cargo holds during voyage

Before loading

- Inspection of holds to ensure they are dry, clean and free of insects

- Inspection of wheat’s moisture content

- Obtain cargo quality certificate

- Obtaining necessary cargo information / instruction of carriage by sea from the shipper

During loading

- Monitor weather

- Sample cargo and check its condition regularly

- Call a P&I surveyor for assistance, if necessary

After loading

- Conduct draft surveys before and after cargo loading

- Seal the hatches properly

- Get a fumigation certificate / instruction from the authority

- Clause B/L in conformity with M/R to protect carriers in case of discrepancies in quantity, damage / shortage / con tamination etc.

During voyage

- Follow the fumigation instruction strictly

- Check the cargo hold bilge, cargo temperature and humidity regularly

- Maintain accurate records

- Ventilate the cargo holds as necessary

- Prevent over-heating to the fuel oil tanks next to the cargo spaces

- Follow the Enclosed Space Entry Procedure strictly

Discharge

- Always be careful when entering holds due to increased CO2 and decreased O2 levels

- Discourage discharge operations in bad weather. If the cargo receivers insist, demand an LOI from them

- Monitor the cargo hold bilge level during the ballasting operation concurrent with the discharge operation

Case Study: The "Giannis NK" [1998] 1 LLOYD’S REP. 337

Facts

- A cargo of wheat and ground-nut pellets were being transported from Senegal to the Dominican Republic

- Under a B/L incorporating the Hague Rules

- On arriving at the port of discharge, an infestation was discovered

- Following unsuccessful fumigation, all the cargo had to be dumped into the sea

- The vessel then had to undergo fumigation that caused a 2 ½ month delay

- The carriers claimed damages against the shippers for the loss caused by the delay and the fumigation expenses

Legal Principles

- Article IV, r.6 of the Hague Rules states that the shipper must bear all damages and expenses that arise directly out of the shipment of ‘dangerous goods to which the carrier has not knowingly consented

House of Lords Decision

- The House of Lords found in favour of the carrier

- The term ‘dangerous’ was not held to be confined to goods of an inflammable or explosive nature

- It was also not restricted to goods that cause direct or indirect physical damage to the vessel or to other goods

- Therefore, the cargo in this case was considered to be dangerous because they were infested and could give rise to the loss of other cargo loaded in the same vessel

With acknowledgment and thanks to:

Andrew Moore & Associates Ltd: www.andrew-moore.com

AVA Marine Group Inc.: www.ava-marine.com

Agencia Maritima Walsh (E.Burton) SRL: www.walsh.com.ar

Messrs. Alberto Martin Azcueta & Assoc.: www.martinazcueta.com

Brazil P&I: www.brazilpandi.com.br