Introduction

High value South American soybean claims continue: soybean carriage advise revisited 2016

The Association has recently experienced a number of high value cargo claims in respect of soybeans loaded in South America, mainly Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, all of which were discharged in China.

This article will discuss in "Section one" the problems associated with soybeans and the dichotomy between local regulations at the load port and different obligations at the discharge port facing the master when issuing bills of lading covering this cargo. It will also explore how those differences impact on the owners' obligations under the charter party.

In "Section two" the article will review relevant load port background information on soybeans and practical loss prevention tips.

Normal, sound soybeans

Skuld would like to thank Brookes Bell who has provided technical guidance and contribution for the preparation of this article.

Section one

Moist soybeans, regulations at the load port and obligations at the discharge port

The common connection

The Association has faced a number of substantial claims arising from cargo loaded at Santos, Brazil and Montevideo and Nueva Palmira in Uruguay.

The common connection for these claims is self-heating due to high moisture content, which can result in discolouration, mouldy and burnt cargo. The main reason for the high moisture content is that South American countries, such as Uruguay, Argentina and Brazil, allow for soybeans with a maximum moisture content of 14% to be loaded on vessels. In most of the soybeans cases registered with the Association recently, cargo was loaded in Santos with moisture content as high as 13-14%.

The high moisture content found in the beans recently is partly attributed to the weather phenomenon known as "El Niño", bringing with it torrential rains in the southern part of Brazil, whereas the centre-west area of the country has sustained drought. Although the local statistics for 2016 are not yet available, claims arising from cargo originating from Santos have been increasing.

A perishable commodity

Soybeans are, of course, a perishable commodity and one cannot expect to store them indefinitely. The concept of "safe storage" is probably incorrect since there is no particular set of conditions under which bulk soybeans cannot be damaged. However, the two crucial aspects are heat and moisture. The period of safe storage (before noticeable deterioration occurs) depends largely on the initial moisture content, the temperature of the beans at loading and the subsequent storage conditions, higher temperatures and moisture content increase the rate of deterioration.

The effect of moisture

The effect of moisture content on the shipment of soybeans has been summed up in a House of Lords Judgment (Soya G.M.B.H. Mainz Kommanditgesellschaft v. White; 1983) which held that:

- It is a natural characteristic of soybeans when shipped in bulk that if the moisture content of the bulk exceeds 14 per cent, micro-biological action, the nature and causes of which are unknown, will inevitably cause the soybeans to deteriorate during the course of a normal voyage from Indonesia to Northern Europe to an extent which will considerably reduce their value on arrival.

- With a moisture content of between 12 and 14 per cent (below 12 per cent no micro-biological action occurs), there is a risk that deterioration from micro-biological action can occur during the course of such a voyage. Whether it does or not depends upon factors that remain unknown. The range of moisture content between 12 and 14 per cent is referred to as the "grey area".

The voyage from Brazil / Uruguay to China

If cargo is shipped at 13% or 14% at the load port, it still has approximately eight to ten weeks sailing time assuming no delays at the load port and no delays at the discharge port. The weather temperatures on route may vary as the vessel transits from one tropical region to the other. Therefore, there is a significant risk that by the time the vessel arrives in China the cargo may overheat and moisture damage giving rise to discoloration, mould or burnt cargo may occur.

What has been happening in China in 2016?

The common problems with the cargo at discharging ports in China are serious discolouration, high moisture content and a large amount of black/burnt beans evenly spread throughout the whole consignment.

Extensive visible mould growth and caking noted at the hot spot in the aft starboard corner

According to the usual practice in China, cargo receivers will seek to reject the damaged cargo but still insist that the damaged cargo is discharged into the receivers' silos/premises for their use/handling. Often little if any segregation of damaged cargo is undertaken before the cargo is put in the silos. This can increase damage claims as cargo interests may argue that once in the silo the damaged cargo can contaminate the good cargo. At the same time receivers will lodge a claim for loss of the whole consignment either against the cargo insurers and/or owners under the bill of lading.

How claims are processed in China

Upon arrival of the vessel at the discharge port Chinese claimants will often apply to the China Inspection & Quarantine (CIQ) for sampling and testing. The test results are usually given to the applicant which are the 'claimants' and not given to the owner if owners do not apply for a joint applicant. It should be noted that CIQ results carry substantial evidential weight in Chinese courts.

Bill of lading holders in China mainly rely on two grounds for their claims in contract against the carriers for damage/shortage:

- The carrier has not cared for the cargo during the voyage hence the loss or damage to the cargo. Here the CIQ report will be very important.

- The carrier omitted to clause the bill of lading, which was issued clean while failing to deliver the goods as per the clean description in the bill of lading.

The significance of the bill of lading

Once Chinese courts determine that the carriers or their agents have issued a clean bill of lading, but failed to deliver the goods clean to the consignees holding the bill of lading in good faith, they usually decide that the carrier should be liable for compensation.

Does the carrier under a bill of lading have any defences under Chinese law?

The Hague / Hague Visby Rules are not enacted in Chinese law. However, under the Chinese Maritime Code enacted 1993 the owner / carrier will have similar obligations but not identical to those found under the Hague and Hague Visby Rules. Likewise, the carrier can enjoy similar defences such as "inherent vice" to that found under the Hague Rules and Hague Visby Rules pursuant to Article 51 of the Chinese Maritime Code which states that:

The carrier shall not be liable for the loss of or damage to the goods occurred during the period of carrier's responsibility arising or resulting from any of the following causes:... (9) Nature or inherent vice of the goods;

If the carrier raises a defence such as "inherent vice", the carrier will bear the burden of proof under the Chinese Maritime Code. This means the carrier will need good expert evidence to show that cargo damage occurred due to the "inherent vice" of the cargo and will also need to provide all the vessel's ventilation records to demonstrate that the vessel was not at fault in causing the damage.

The dichotomy between Chinese law and English law and laws operating under Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina

Under Chinese law, the owners are obliged to clause the bill of lading in accordance with the condition of the cargo as loaded on board and as known by the master. Traditionally, this would mean the apparent condition of the cargo. That means what the master can see, smell and observe. However, it has recently been suggested by some Chinese lawyers that if the master also knows something about the cargo and if it affects the cargo condition, he may be entitled to insert that in the bill of lading. In this case, that could mean that the master, if he knows the cargo is loaded at an average of 13% or 14%, may be entitled to note that on the bill of lading. The advantage of this is, at least in so far as the BL holder is concerned, that he is then placed on notice of the high moisture content of the cargo and this may aid an inherent vice defence in local courts. We believe he could state something along the lines of:

"Cargo loaded at 14% max moisture as per Shippers Certificate attached: cargo in apparent good order and condition" (assuming at the time of loading cargo was in his visual opinion in good order and condition).

The advantage of inserting this clause on the bill of lading would be to assist owners in Chinese courts with a defence of "inherent vice".

Legal perspective under English law

As stated above, under English law it is well known that soybeans with a moisture content of between 12% and 14% may self-heat. Whereas, if the moisture content is in excess of 14% self-heating is highly likely (depending on the voyage times, etc.).

Laws applicable at the load ports

Pursuant to a standard specification in South American sales contracts and under the Brazilian, Venezuelan and Argentinean law, the moisture content need only be 14% or less.

Problems often arise in South America as it is both common and legal for the moisture content to be 14%. As seen above this exposes owners to a risk that cargo will self-heat during the long voyage, especially given the fact that the transit takes between eight to ten weeks and delays can occur at subsequent load and discharge ports.

The masters dilemma: Clausing of bill of lading and mate's receipts

One of the major problems encountered by owners is that even though it is well recognised that there is a risk cargo may self-heat if moisture content is above 12% but below 14%, owners are probably not entitled under English law to clause the bill of lading and mate's receipts to reflect the moisture content of the cargo, unless it is apparent from a visual inspection that the cargo is not in apparent good order and condition. In this respect:

(a) It was held in the leading case of The David Agmashenebeli [2003] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 92 that the master's duty in respect of the clausing of bills requires that he "should make up his mind whether in all the circumstances the cargo, in so far as he can see it in the course and circumstances of loading, appears to satisfy the description of its apparent order and condition in the bills of lading tendered for signature."

(b) The test is therefore concerned with the visual appearance of the cargo, and not its other characteristics such as its quality or, in our case, its moisture content, assuming characteristics are not apparent on a reasonable visual inspection.

(c) Although it is possible that, in future cases, it may be held that a master is entitled to clause a bill of lading where he is aware of a problem with the cargo, even where that problem is not visually apparent, that would require an extension of the law which based on present case law is unlikely.

(d) If the cargo smells (which can happen with moist cargo) the master is entitled to take note of that and clause the bill of lading.

The Chinese position

Members will recall earlier in this article that under Chinese law to be protected, owners may be entitled to clause the bill of lading to reflect what is known about the cargo. This is a broader obligation than noting the apparent condition of the cargo and would in this case include moisture content above 12%.

Article 75 of The Chinese Maritime Code states that "If the bill of lading contains particulars concerning the description, mark, number of packages or pieces, weight or quantity of the goods with respect to which the carrier or the other person issuing the bill of lading on his behalf has the knowledge or reasonable grounds to suspect that such particulars do not accurately represent the goods actually received, or, where a shipped bill of lading is issued, loaded, or if he has had no reasonable means of checking, the carrier or such other person may make a note in the bill of lading specifying those inaccuracies, the grounds for suspicion or the lack of reasonable means of checking".

Article 76 states that "If the carrier or the other person issuing the bill of lading on his behalf made no note in the bill of lading regarding the apparent order and condition of the goods, the goods shall be deemed to be in apparent order and condition".

The position in Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay

Shippers are allowed by law to ship cargo with up to 14% moisture content. It is not clear though whether the shipper would be entitled to reject a bill of lading issued by owners which stated:

Moisture content of 14% as per shipper's declaration – cargo in apparent good order and condition.

Given the bill of lading states cargo in apparent good order and condition we cannot see how shippers could object to that description.

What can owners do to protect themselves?

If such circumstances arise, there are certain options that members can take.

1. Owners can insist on clausing the bill of lading and mate's receipts

The advantage of this option is that it should minimise the risk of any cargo claim in the discharge port, as the receivers will have been made aware (at the time the bill is consigned or endorsed to them) of the excessive moisture content prior to shipment.

However, there is no authority yet which would support the clausing of the bill of lading and mate's receipt in these circumstances. As of this moment the law is untested on this point. The authorities appear to provide for clean bills to be issued where the cargo is visually and externally in a good condition. If owners insist on clausing the bill of lading and mate's receipt, they may be in breach of charter (which could lead to substantial damages, if, for example, this prevents compliance with the terms of the Letter of Credit).

To avoid this dilemma, we strongly recommend that owners should insist on a protective clause in the charterparty allowing owners to insert the moisture content if above 12% on the bill of lading.

2. Owners can issue a clean mate's receipt and bill of lading

The advantage of this option is that it will avoid any further dispute or delay at the load port and under the time charter party.

The disadvantage (which is a very substantial disadvantage) is that if some of the cargo self-heats, owners may face a very large cargo claim at the discharge port. Although, as a matter of English law, there should be a good defence (on the basis of "inherent defect, quality or vice of the goods"), such a defence may not succeed in discharge ports such as China. As advised earlier, if the high moisture content was known at the time of shipment there may under Chinese law be an obligation to state that on the bill of lading.

Further, even if the claim is defeated in China on the basis of inherent vice owners could still incur significant expenses and inconveniences (if, for example, the ship is arrested). Delay while the vessel is arrested can cause hire disputes with charterers arguing the vessel is off hire and owners insisting the vessel is on hire.

To resolve these issues, we recommend owners carrying this cargo insert a protective clause in the charter covering who is responsible for delay, costs associated with arrest and providing security and legal and associated costs if cargo in excess of 12% is shipped on board the vessel.

Section two

Background information and practical loss prevention tips

Background information on the load ports

How is the soybean cargo transported and stored at the load ports in Brazil prior to shipment?

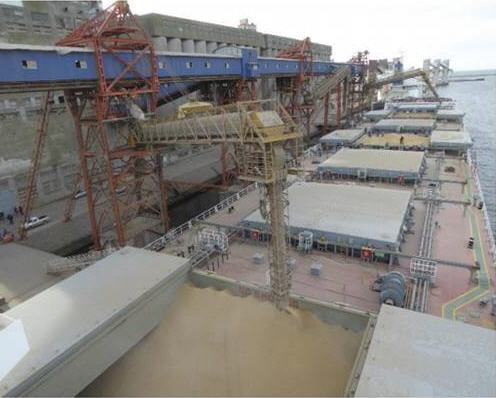

Soybean cargoes are usually transported to the loading port by truck and railcar. For some of the riverine ports in the north, cargo is usually received by river barges. When at the port, the cargo is loaded by means of conveyor belts from the warehouse to the vessel and there are times where the belts are wet due to previous heavy rain. This contributes negatively to the moisture content of the cargo.

Loading and trimming continued by two gangs until completion

Soybean cargoes are usually stored at the load port silos for periods not longer than one or two months. The biggest exporting firms in Brazil are ADM, BUNGE, CARAMURU, CARGILL, NOBLE and DREYFUSS.

Montevideo / Nueva Palmira, Uruguay

Similar to Brazilian soybeans, during loading operations, the Association has been advised that the moisture content of the soybeans in Uruguay are also high, ranging in between 12% to 14%.

How is the transportation and storage in Uruguay prior to loading?

In Uruguay, normally the soybeans are transported from the farms to the storage facilities by trucks. As of March 2016, there are 334 storage facilities in Uruguay, 42% of which are located near the main grain exporting ports of Montevideo and Nueva Palmira. From there, internal transportation and storage practices for each port varies according to the terminal to be used.

Soybeans loaded in Uruguay may have been originally grown in neighbouring countries such as Argentina, Paraguay and occasionally Bolivia. The Uruguayan-grown beans may be delivered to Nueva Palmira terminals by truck or rail, but the cargo originating elsewhere is more likely to be delivered by river barge and transhipped via a loading berth or dolphin to the sea-going vessel.

In Montevideo:

- No silos inside the port

- Soybean cargo is transported from the stowage facilities to the port by trucks

- Montevideo is a multipurpose port - there are no fixed means to load grains

- The grains are discharged at the pier into repositories and loaded on board using portable belt conveyor systems

In Nueva Palmira:

- There are two grain terminals: "Navíos" and "TGU"

- Both terminals have silos and fixed conveyors to load/unload vessels

- Soybean cargo is transported from farms to the terminal storage facilities by trucks or by barges from other smaller ports in Uruguay

- Some floating transfer stations are available where the vessel berths and the grains are transferred from barges to vessel by means of grab

Segregated cargo in the receiver's warehouse

The main exporting firms in Uruguay are Crop Uruguay, Barraca Jorge Walter Erro, LDC Uruguay, GARMET, Cereoil.

Loss prevention tips

At the load port

The Association suggests given the high value of this cargo and the recent problems with moisture of the beans on shipment that a local surveyor is appointed to monitor loading. The local surveyor should be briefed and asked to do the following:

- Ascertain what were the weather conditions that applied to this crop?

- Was there much rain?

- Inspect the cargo throughout loading, recording visual appearance, odour and – in particular – cargo temperature throughout.

- Is the cargo in apparent good order and condition, or are there specific concerns about the condition of the cargo?

- If so, the surveyor will need to assist the master in preparing letters or protests and/or clausing the mate's receipts and bills of lading.

- Was the cargo delivered by barge? If so, what was the route? Was the barge covered?

- Speak to the shippers and their superintendents to collect information about the pre-loading history of the cargo. If the cargo is loaded from silos – what are the harvest dates? How long has the cargo been in the silos prior to loading? Were intake samples tested for moisture from the lorry deliveries to the silo? Are temperature logs available during silo storage?

- If the cargo is loaded from barges, inspect the barge cargo prior to transhipment for signs of heating, mouldiness, off-odours etc., and carry out a temperature survey in each barge prior to transhipment. Where and when was each barge loaded? Are barge quality/moisture certificates available? When was the cargo harvested?

- Observe and describe the sampling operations carried out by shippers' superintendents. How and where are they taking samples? At what sampling frequency? What final samples are being prepared? Obtain a copy of the sampling protocol, if possible.

- Record weather information during loading, including rain and temperatures. In case of rain, is the cargo adequately protected prior to loading?

During the voyage

1. Monitor cargo temperature

The crew should record the cargo temperature at the time of loading. This should preferably be done with a digital thermometer and thermocouple probe. If the ship does not have these but is carrying the cargo, we recommend that these are purchased and put on board the vessel and that the crew are trained on how to monitor them. Such information will help cargo experts should problems arise in determining how much the temperature has increased and it will be providing information to assist cargo stability. Further this information can be used by owners when defending cargo claims at the discharge port.

2. Ventilation

During the voyage the master should ideally apply ventilation (after the period of fumigation has been completed). It should be noted that natural ventilation as found on bulk carriers affects only the top 10 to 20 cm of the surface and whilst at sea basically equates to moving humid moisture laden air, with 80% to 90% relative humidity, across the surface of the stow. However, it is frequently alleged in Chinese courts that the crew applied improper ventilation and that this caused the cargo damage. Therefore, it is extremely important for the crew to maintain an accurate ventilation log with temperatures and dew points.

Ventilation, either mechanical or natural, is designed to regulate the conditions in the head spaces of the cargo holds and as such has an effect only on the surface layers of a stow. It is not capable of removing heat or moisture from deep within the stow.

Discharge as quickly as possible

The only thing that can be done to control the self-heating is to discharge the cargo as quickly as possible and to place it in a silo where it can be properly cared for, or better, processed promptly into oil and meal.

Points to note at the discharge port

- In the event the cargo is loaded with a high moisture content above 12%, we suggest that a surveyor is appointed at the discharge port to attend the vessel throughout discharging operations.

- The surveyors should take samples and gather evidence for preparation of any anticipated claims.

- Segregate cargo and make sure the cargo of different specs is not mixed.

- Monitor quantity of the different spec cargo discharged.

- Keep all vessel records and preserve documents, such as ventilation and log books.

Reference is made to several previous articles on this cargo issued in our Beacon magazines and on our web site.